22: Moving Pieces

A room where the art, and the artist, feel perfectly at home. A conversation on starts. An exploration of the Calder Tower at the National Gallery in D.C.

Notes

The Art:

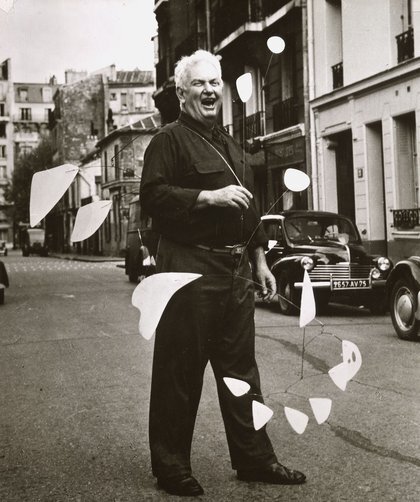

This episode talks about a number of pieces from the life of America’s greatest sculptor, Alexander Calder. Calder is most well known for his mobiles, giant hanging pieces that move subtly with the currents in the room. All of the pieces discussed in this episode are in one room, Tower 2 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.. It’s free to visit, so if you’re ever in D.C., make sure to go visit!

Sources:

All of the quotes from Calder in this episode come from Calder: An Autobiography with Picture (1966). Additional research came from Calder: Conquest of Time by Jed Perl.

Discussion Questions:

Where does your story with the world of art start? When was the first time you felt the urge to create? When was the first time you went to a museum?

Can you think of a piece, or a museum/gallery space that fills you with joy? How do you let the joy of things around you move you? In what ways do you prevent joy from moving you?

If you could ask one other artist how they got their start, who would it be and why? What other questions would you ask them?

Giveaway:

We are having our first giveaway here at Accession. We don’t pay to advertise this show, so we need your help to spread the word. Tweet about the show or share us in your Instagram story with the #accessionhomeward, and you’ll be entered into our random drawing. One lucky winner will win an exclusive season two show art print, signed by myself and V Silverman. And another winner will win a copy of Calder: The Conquest of Time by Jed Perl, a beautiful biography with gorgeous pictures that I used extensively in researching this episode. Again, tweet about the show or add us to your instagram story with #accessionhomeward to win. And you might just hear us shout you out on the next episode of Accession. Our winner will be announced next month. Good luck!

Support:

Visit AGTrapHaus to bring their art into your home today.

Credits:

This episode features Steve Vineberg as Alexander Calder, Alex Welch as Aline Bernstien, Charles Gustine as Piet Mondrian, and Ana O’Daniel as Marcel Duchamp. Our theme music is played by Mike Harmon, with recording and production by Casey Dawson. This episode features music by Blue Dot Sessions. Our season two art was made by the incomparable V Silverman. This episode was written and sound designed by me, T.H. Ponders, and produced by myself and Ana O’Daniel. Our executive producers for this season are Charles Gustine and James Oliva.

Episode

Welcome to Accession. Today, we’re at the East Building of the National Gallery in Washington D.C. Once you’re in the east building, take your time winding up to the very toppest of top floors, enjoying the sharp angles and turns of I.M. Pei’s building. Now the top floor, consists of three spaces. Two towers and a rooftop terrace with a giant blue chicken. We are looking for Tower Two, which houses the largest collection of Alexander Calder’s art in the world. And while we won’t be talking about any one of these pieces specifically, I’ll let you in on the secret that one of my absolute favorites is National Gallery accession number 1996.120.3, Black and White and Ten Red.

This room was one of those beautiful, happy accidents that occur all too often in an art museum. You go in search of one thing and happen upon a completely different treasure. Come to think of it, when I first found the room we were actually looking for, it was the exact same sort of happenstance. But as our wanderings would have it, on this particular journey, we first found ourselves in this, the Calder Room.

Now, it’s no strange thing to find one of Alexander Calder’s mobiles hanging in an art museum. Finding his art in museums is such a common occurrence that at one point when I was a kid, I remember thinking “I should remember Calder’s name, so that I can identify his mobiles when I go to new museum. That will impress people.” Actually, I had this thought multiple times before I finally committed it to memory. I recommend you do this too- you’ll win a lot of points in an art museum if you can call out a Calder. And there will be a Calder.

But there won’t always be a room full of Calder. This is truly something special.

The room is a giant hexagon, with a great glass ceiling composed of frosted triangles that let in the soft white light of the sky and the deep blues of clouds passing over head. The room only has a few yellow accent lights, so almost all the light in this room comes from that ceiling. In the middle is a giant black sculpture, called “The Great Ear” and a few of his small animal sculptures sit on the floor around it. Around the room are a few of his paintings and some display cases with some of Calder’s smaller statues. But the most exciting part of the room are the mobiles, the moving sculptures. From that high, glass ceiling hang about half a dozen of Calder’s mobiles, abstract shapes cut out of sheet metal, painted in simple colors, and connected by wire and hook. These mobiles perfectly capture a combination of the artificial yellow and natural blue and white lights, and shine as they spin. This room is set up to dance.

Of course, none of these mobiles are set to move by motors or gears. They move solely on the currents of the air in the room. And so my favorite part of this room is actually those two doors you came in, which, every once in a while, find themselves both open at the same time, letting the room take in a breath, and setting each mobile into a new rhythm, a fresh start. And therein lies the perfection of this room: as the sun and the earth turn round each other, as the mobiles spin ‘round their axes, as you wander around this room, and others wander in, it is absolutely impossible to look upon any one point and see the shapes and colors and lines and shadows cast by the mobiles in anything but an absolutely unique configuration.

Only once before, in that other room we were looking for coincidentally, have I ever felt like the experience that the museum was providing aligned so perfectly with what I knew about the creator— like the art, and the artist, really felt at home in this space.

Calder: Well, it’s no Painter Hill Road, but they’ve really captured it all here. Is it true that this is the single largest collection of my work in the world?

Ponders: All here, mobiles, stabiles. They even have some of your paintings.

C: Remarkable.

P: While you’re here, I don’t suppose you’d mind a couple of questions?

C: Ask away. I’m an open book. But I should warn you- once you get me started, you might just have to suffer my whole story.

P: There will be no suffering, I can assure you. I love a good story, and from what I can see in this room, you are a master storyteller. So, where did it all start?

C: Well the first of many starts happened sometime nine months before my being on this earth. But I suppose you’re more interested in my start into art.

P: Yes, your start into art.

C: There were many starts- false starts, head starts- I grew up to artist parents, who wanted nothing more for me than to not try to make art my profession. Of course, this isn’t one of those situations where my parents forced me into law and I became an artist as some act of rebellion. They always let me create and tinker and make my art. Every home of the many we lived in had some space for me to call a studio.

P: So they were supportive?

C: Oh very supportive, right up to the moment where every parent has to stop supporting you in the swaddling way and start supporting you in the pushing you on way. I think that moment occurred the day my father said the words “What do you want to study?” You can imagine I was fairly nonplussed. But a fellow at Lowell High School, Hyde Lewis was his name, told me he was going to be a mechanical engineer. I wasn’t sure exactly what he meant by the term, but I thought I’d better adopt it, for no better reason than to give my father an answer.

P: So you went to engineering school, decided it wasn’t for you, and leapt into the art world?

C: Not quite. But engineering did put me firmly in a position to make art later, and make good art. Following school I worked any number of odd engineering jobs. Until of course, that fateful job that would change my life forever. Maybe the second most important moment of my artistic life.

P: Oh! The H.F. Alexander!

C: Oh!? You know the story! Then I’ll just skipped forward to the part with Mondrian...

P: Oh no, no. Tell it anyways. It’s my favorite part of your story and I’d love to hear you tell it.

C: Well... if you insist! It was the Spring of ‘22, and the H.F. Alexander was looking for a crew to sail the vessel from New York City to the West Coast, where it would then become a passenger craft- and eventually the fastest passenger boat on the western seaboard. Well I made the right phone calls and pulled the right strings and got a job as an engineer on board. Quite a large ship. It carried over seven hundred passengers and a crew of about a thousand. It was early one morning on this voyage from New York to San Francisco. The sea was calm sea. We were just off the coast of Guatemala, when over my couch— a coil of rope that was comfortable enough to sleep in— I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise off one side of the boat and the moon looking like a silver coin off the other. Of the whole trip, this impressed me most of all. It left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system.

P: Did you know then?

C: Know what?

P: That it would lead to all this.

C: Oh! I think it’s one of those things that you know even before you know that you know. I knew it enough to hold it close, and I know it enough now that when you ask for the start of it all, it really feels like that could have been it.

P: That makes a lot of sense. I’ve certainly had those moments that only make sense in retrospect. Did you stay with the H.F. Alexander long?

C: No, soon after we arrived in San Francisco, I made my way by boat up to Washington, round past Cape Disappointment and into Willapa, where I continued from there by but to Aberdeen to visit my sister. I got a job in the logging mills, putting my engineering to some use. It was there, amidst the woods and hills and beaches of the Olympic Peninsula that I rediscovered my need to create, my desire to make art. It’s an inspiring place.

P: It truly is. I’m still amazed that in one part of this country, you can be so quickly dwarfed by snow-covered peaks, giant moss-covered trees, and the vastness of the Pacific, all mere miles apart. I go back to Ruby Beach in my memories all the time.

C: Truly a place of tremendous beauty, and through the advice of some colleagues, I felt the urge to paint it. I sent for some supplies, and, if you’re looking for my true artistic journey, I suppose it can be said to start here.

P: But you weren’t making the mobiles yet? That wouldn’t be for some time?

C: No, I got my start the same way every artist gets their start. I moved back to New York and did everything I possibly could. I drew, I painted, I sculpted, I made toys. Anything anyone would pay me to do. I made these wire animals and people that you see on the floor over here. Eventually I made the Circus, this set of wire sculptures and pieces I could use to act out all the joys you can find in the bigger version of the circus. I took that thing everywhere and would find any excuse I could to perform with it for an audience. I can still tell you the reaction of every person who ever commented on the circus. Some people were filled with tremendous joy by it. Others just found it boring, I suppose. I was once invited to perform the circus for the friends of Mrs. Aline Bernstein, up on Park and Maddison. When I had finished the show, she said only one thing to me.

Mrs. Aline Bernstien: “It’s... a lot of work.”

C: That was her only comment. And her sister said nothing and only asked where I had gotten the Bergdorf Goodman suit box that I kept it in.

P: Oh I’m starting to see where the “suffering” of the story comes into play.

C: Oh yes I could go on about that circus for hours. It was such a joy to perform, and did really carry me through those early days of my career. I mean, without that circus, I might never have met Louisa, my wife, or have found my way into the circle of artists that would also be my closest friends; the likes of Fernand Leger, Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Piet Mondrian.

P: You jumped back and forth between Paris and New York quite a bit, yeah?

C: Oh yes. Every chance I could. I found such good company in both. I suppose it only makes sense that I found my greatest company, Louisa, on one of my return journeys from Paris. Her father had just taken her to Europe to mix with the young intellectual elite. All she met were concierges, doormen, cab drivers— and finally me. It would be a couple of years before we were finally wed, but from that boat ride on, she was a constant companion in my life.

P: Yet another start?

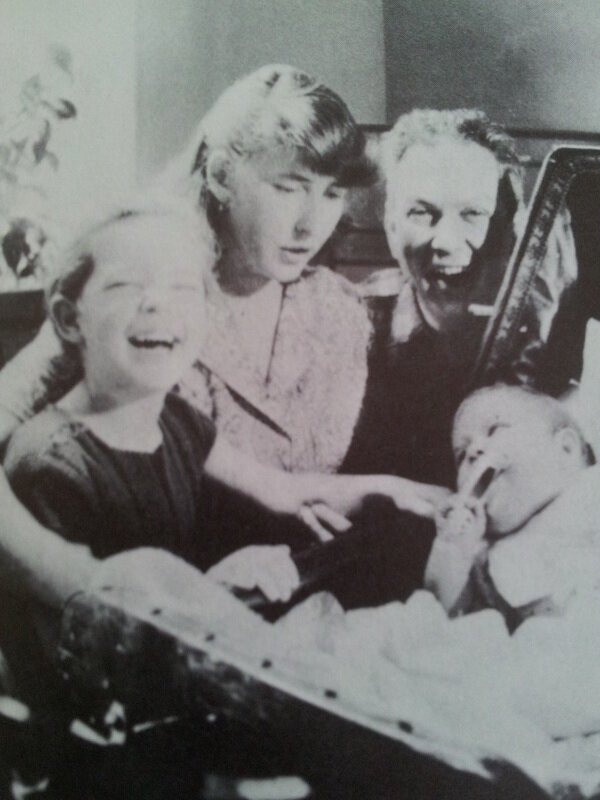

C: The most important. The start of my perpetual joy-- my family. We were married, and eventually purchased our home on Painter Hill Road in Roxbury, Connecticut. Louisa had had some complications with a pregnancy when we were first living in Paris, so when we were trying to have our first child, she stayed with her mother in Concord. I shuttled that long stretch between Roxbury and Concord every week.

P: Another part of the country I know all too well. I’ve made that drive across Northern Connecticut more times than I can count. There is a deep, simple beauty in those woods.

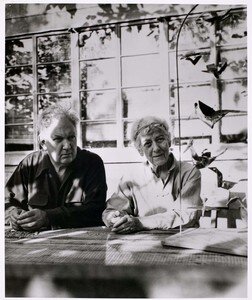

C: There really is. It’s the kind of canvas upon which an artist can work. I converted the barn at Painter Hill Road into my studio. In the winter the sun would come in from the south into the great glass windows and warm the building, and in the summer, it would beat down from directly overhead, setting the studio in total cool and shade. Eventually I set up a bunch of eye hook screws from the ceiling, so I could set the mobiles up in any configuration and order. That barn, and Painter Hill Road, truly became the home of my creation and my joy.

P: But Paris!

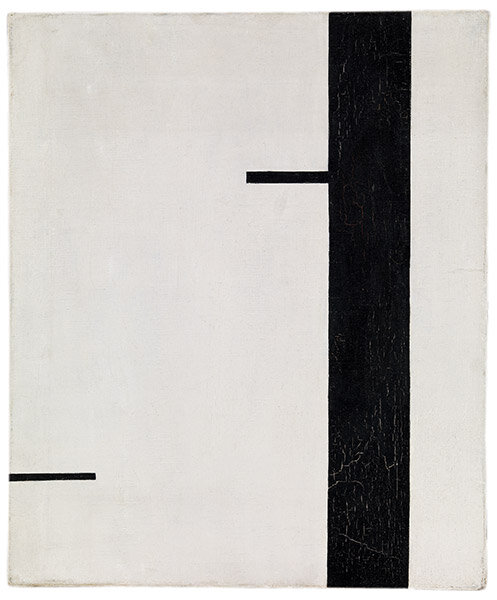

C: Oh! Right! Paris! I’m sorry I tend to wander from one idea to another. But yes-- it was in Paris that I met some of the artists who were most influential to my own craft. None more so than that first visit to see Mondrian. That visit gave me a shock. A bigger shock, even, than eight years earlier, when off Guatemala I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other. You remember the story?

P: I do!

C: Mondrian lived at 26 rue de Depart. It was a very exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid walls between the windows there were experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked on. Even the victrola was painted red. I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said...

Piet Mondrian: “No, it is not necessary. My painting is already very fast.”

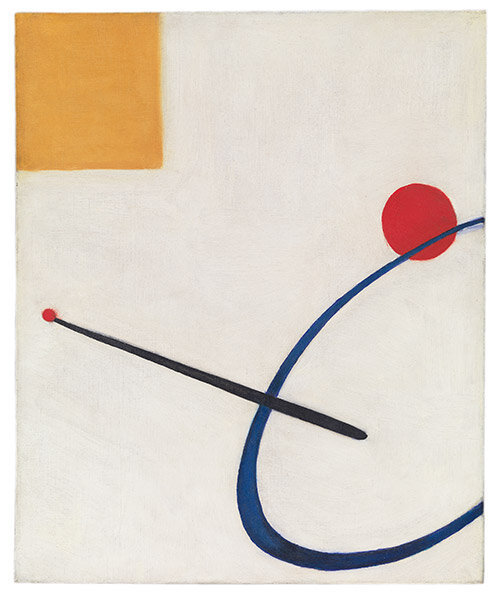

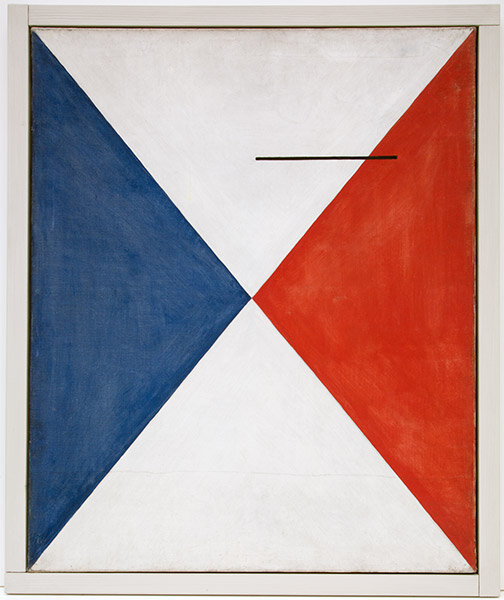

C: This one visit gave me the shock that truly started things moving. Though I had heard the word “modern” before, I did not consciously know or feel the term “abstract.” So at thirty-two, I found that I wanted to try something new. I wanted to paint and work in the abstract. And for two weeks or so, I painted very modest abstractions. Which you can see right up there on the walls.

P: Oh! Now that you mention it, I can really see Mondrian’s influence. They have the same simplicity and eloquence of a Mondrian but with...

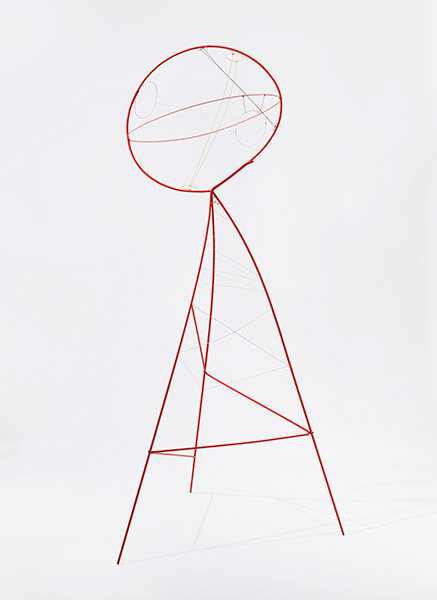

C: Motion! Precisely! But of course, I could do more. I took my wire, and some thin sheets of metal painted in those bright primary colors and viola! Another start for you.

P: Another start indeed.

C: Initially I had set the things up with motors, but I quickly abandoned that. The grease was too messy, and the motors a bit too predictable. It means so much more if you let the natural air of the room set their motion.

P: And the name?

C: Ah yes! Marcel Duchamp was instrumental in organizing one of my first exhibitions of these things in Paris, and when I asked him what sort of a name I could give these things, he at once produced...

Marcel Duchamp: “Mobile. It has a double meaning you see. Not only something that moves, but in french it means motive.”

C: A year or so later, Jean Arp misremembered the name of mobiles, asking if the things I had made for the show were called “stabiles” and from that lapse in memory, a whole separate direction in my artistic career was started.

P: Were there any more starts after that?

C: Oh I could go on an on with the stories of my life. Each one a start, in its own sense. Take for instance the war. I went to DC to see Saint-Gaudens, the son of the sculptor. He was the head of camouflage, and I had intended to use my artistic skills to be a camoufleur. The sent me onto the base, drove me round in circles, and then told me to report at another base in New Jersey. But there was very little for me to do, and eventually I just packed up my things and went home. I later found out the same day that I left the war effort was D-Day.

P: And did you ever meet with Saint-Gaudens?

C: If I had seen Saint-Gaudens, he’d have been a poor head of camouflage.

P: Touche.

C: But of course, it was during the war that pieces were very scarce. It led to mobiles with much smaller nodes, which I called Constellations, like that one over there by the door, and a few smaller wooden stabiles, like those ones in the glass case there. I stayed mostly abstract, but occasionally dipped back into my roots, like this lovely fish hanging up here.

P: Well I must say, that is quite the answer to the question “Where did it all start?”

C: I gave you a fair warning. Start upon start upon start. A thousand little stories across my life, each another point for the wind in the room to catch me, and set me moving in a different direction. Any other questions before I go?

P: Well, I guess my second question seems like it should be the longer, more complicated one, but now I’m not so sure. I had initially thought of asking why. What do the mobiles mean? What were you trying to tell us? But I think the answer to that is fairly clear now.

C: Oh? I would love to hear.

P: Well, it seems to me, just listening to you tell your story, that all of life is made up of the very same pieces we see in this room. The stabiles and the mobiles; the parts that anchor us, be it to the ceiling or the floor, and the parts that are there to catch us, to inspire us, to set us dreaming. And the wind in the room, the thing that happens every time someone steps through those doors there, is pure joy. Joy isn’t something that we have inside of us. It’s around us constantly. And the more pieces we are connected to, the more people we bring into our lives, the more points of contact we have with the joy. And if we only let it, it will start us dancing into shapes and colors and lines that no one has ever seen before, and no one will ever see again. Joy: the catalyst of perfect uniqueness and beauty. A bit like the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other. How does that sound?

C: It sounds like a good start to me.