7: Lessons of Illusion

We take a look at Gene Davis' Lemon Look, and explore why humans are so fascinated by illusions, and what we have to learn from them.

Welcome to Accession.

Today, we're at the Worcester Art Museum, and we're going to head back to the modern art section. Follow the knight on the pink horse up the stairs, to the right of King Hamlet, in through the dark doors and past the rocket’s red glare. But this time we are going to move beyond the room that is grounded in images that look like things we know to be real. We are going to move into the world of the wholly abstract; Or, rather, the room of the wholly abstract. Go on from here, beyond the human-whale legs and the ringing video, into this next room which is very colorful and very geometric. You should see a giant piece in the back that looks like three orange ovals that have been smooshed together, and the one that we are here to see today. It may just look like a lot of stripes, but I think it has an important lesson to teach us. Today, we're looking at Worcester Art Museum, accession number 1981.344, Gene Davis' Lemon Look.

If you've been anywhere on the internet in the last week you've probably heard this audio clip at least a handful of times.

And, depending on any number of factors, you are currently hearing a robotic voice saying either Yanny or Laurel.

A similar video, though slightly less popular, went around the internet this last week as well, this time of a green glowing rock. In this audio clip it's going to say brainstorm:

And in this audio clip it's going to say green needle:

And in the clip, the same clip I have now played for you twice, it is either going to brainstorm or green needle, depending on which one you are thinking of. Go ahead and choose one, and...

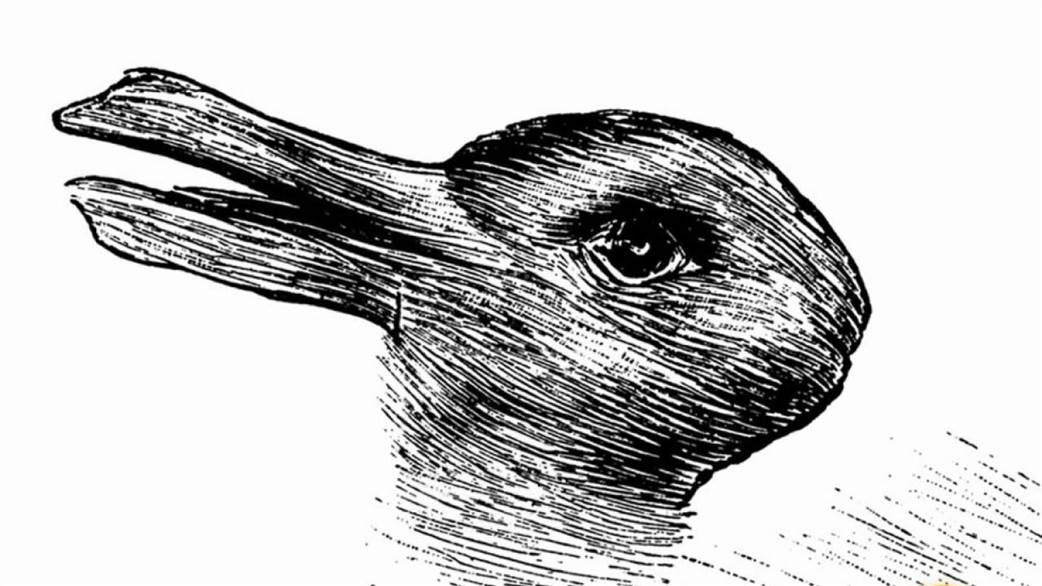

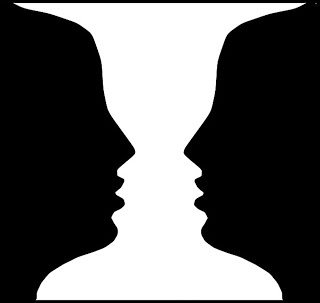

Weird, right? Now I'm sure that you the listener are also familiar with a variety of other optical illusions, like a rabbit that may also be a duck, or a duck that may also be a rabbit, or maybe two faces looking at each other whose inverse forms a vase.

These common illusions have probably come up at some point during either your education as children or during a seminar on teamwork as a metaphor for how we all see things differently and it's all about perspective. Don't get me wrong, it is true that we all see things differently and it is all about perspective. I'm definitely not contesting that. But what I want to dig into the bridge. I don't think illusions, optical or auditory, are designed to teach us that it's all about perspective. At least, that's not the primary lesson of illusion. For that, we have to turn to art.

Now art is full of illusion.

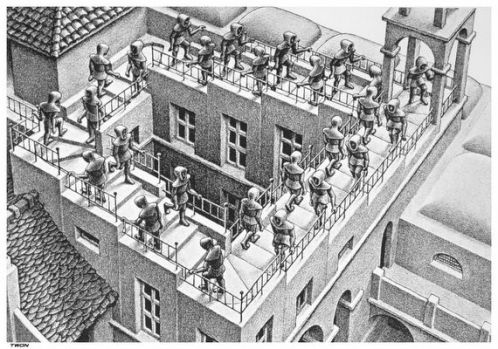

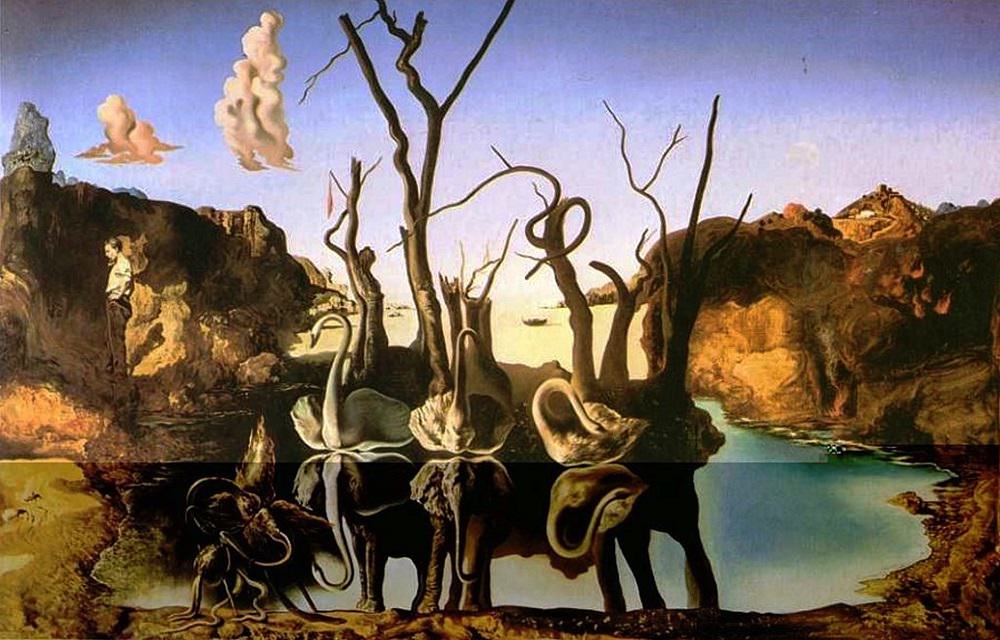

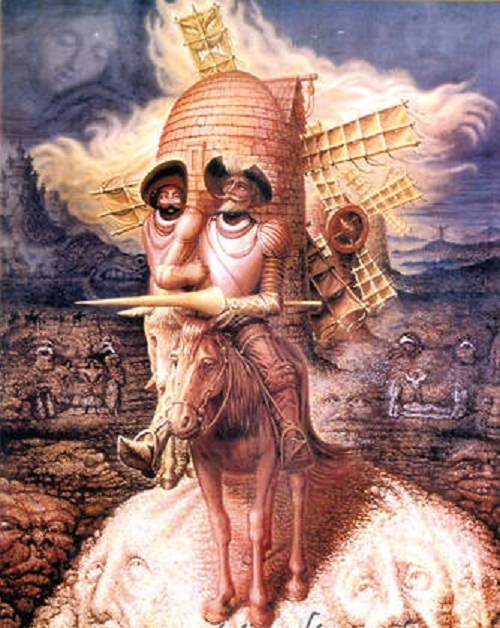

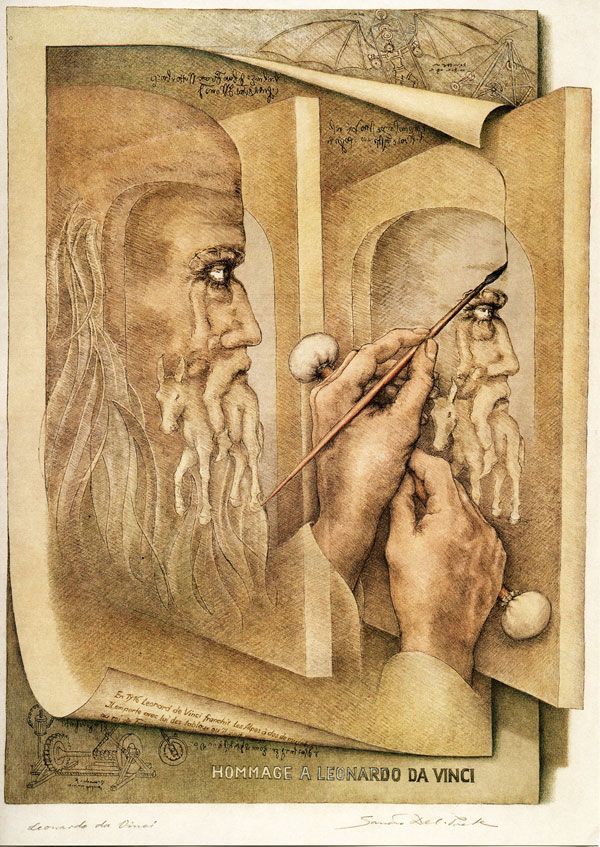

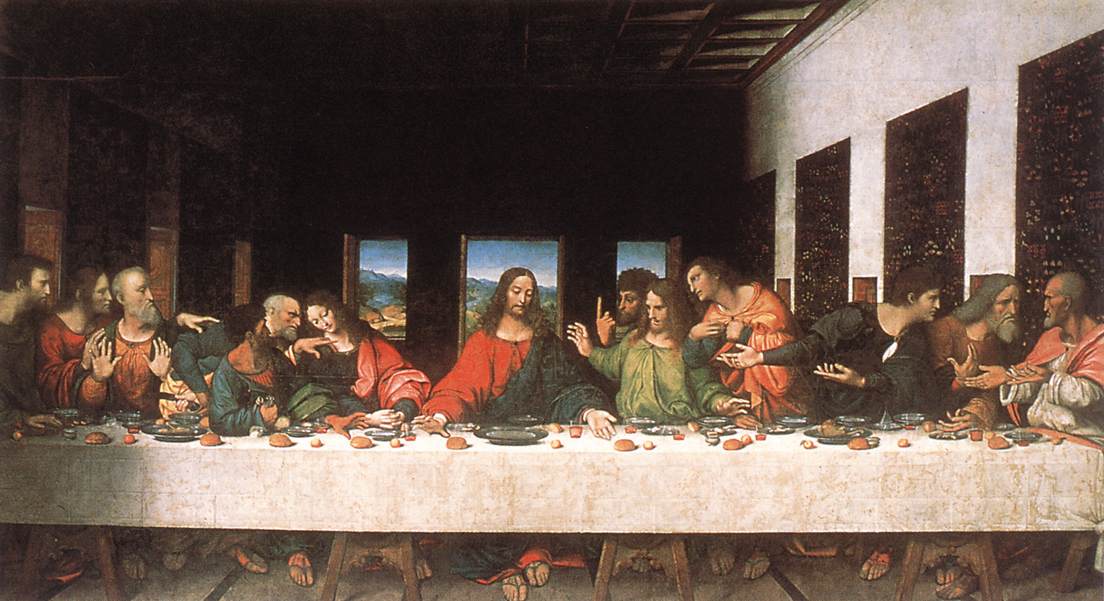

There are the obvious cases, painter's whose main focus is making things that seem to break reality, or metamorphose one thing into another. (Escher and Dali are the chief among these, but we can look also to many others, like Octavio Ocampo or Sandro Del-Prete) But more commonly and less obviously is every piece of art that purports to convey three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. Our ability to create that feeling of depth and dimension on a flat canvas is one of the greatest illusions that artists have been pulling off for centuries. But we can even look beyond the simple illusion of depth into the more modern fields of photorealism and hyperrealism, with artists like John Baeder or John Pugh, which aim to make the fiction as close to the reality as is technically possible. This kind of illusion doesn't rely on our mind seeing one thing instead of the other; Rather, it relies on the mind knowing one thing to be true about reality, and experiencing the opposite.

But these techniques in art don't break our brains in the same way as illusions do. They don't give us that sensation of an illusion that feels like someone is tickling your brain, but they’re intentionally not trying to. They are trying to dull that tickling sensation as much as they can. A piece of art that uses the illusions of depth or realism is trying really hard to hide the fact that they are unreal and flat. It is much easier to feel this tickling when a piece has nothing to hide, when it revels in being both unreal and flat.

Enter abstraction. And, in this case, enter Lemon Look.

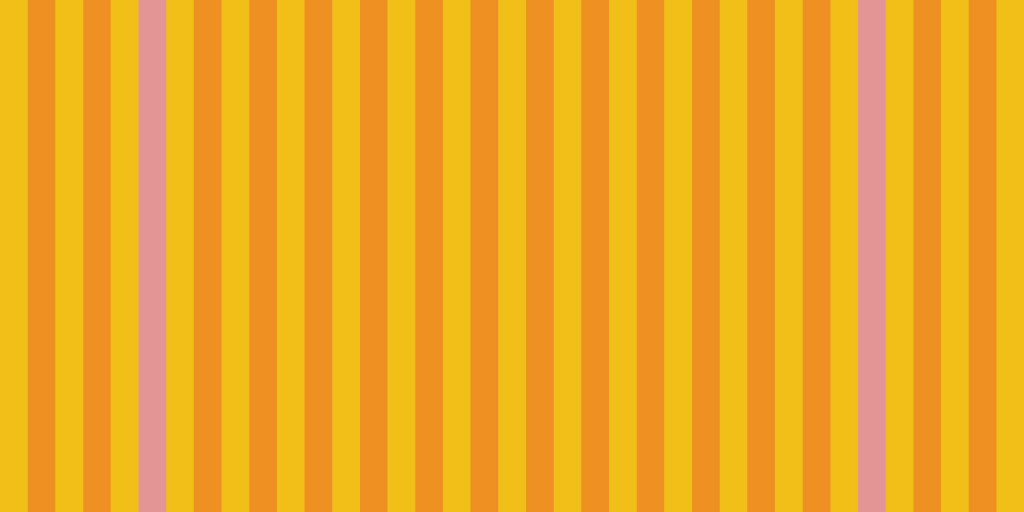

I want you to look at all the colors in Lemon Look. The majority of the canvas is yellow and orange alternating stripes, but five stripes in on either side, where the pattern dictates a stripe of orange is a stripe of pink. These are the only colors on the piece, and the existence of these three colors is what I want you to hold in your head as the reality.

Now, align yourself with the center of the painting and take a few steps back, about five feet. If you're looking at the painting on a screen, this will still work, but you'll have to mess around with the distance. Pick a point in the center of the painting, be it yellow or orange, and stare at it for as long as you can without blinking.

If you're doing this right, and your eyes are not moving, or moving very minimally, then the pink stripes should be fading away and being replaced by orange stripes. Some people report that the pink stripes entirely vanish. For me, they sort of phase in and out. And it makes my brain tickle in the most delightful way. And this is precisely the tickling that an illusion can cause us.

But let's take this a step further. As you look at the canvas, as you stare at that center point, try to hold onto one or the other, either the perception or the reality. Even though you do not see the pink stripe, hold onto your belief that the pink stripe exists. Or harder yet, even though you know that the pink stripe is there, try to believe that it does not exist.

Now Lemon Look was painted by Gene Davis, who belonged to a school of painting known as the Washington Color Painters, and who painted many, many striped canvases just like this one. He is a man whose life and ideas deserve much more of our time, and whose work is begging for a much deeper analysis than simply turning it into an optical parlor trick, and we will give him both of these in an audio story that is far down the line but already steeping. However, I don't think we've gone too far astray from how he would have wanted us to view his paintings. If you read the card, it will provide you with this brilliant quote from his 1975 interview with Donald Wall:

“...look at the painting in terms of individual colors. In other words, instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color such as yellow or a lime green, and take the time to see how it operates across the painting. Approached this way, something happens, I can’t explain it. But one must enter the painting through the door of a single color. And then, you can understand what my painting is all about.”

We've entered the painting through the yellow in the center, and we've seen its rhythm and echo across the painting as it distorts our known reality and presents us with a new, equally plausible one. But while you're here, take a moment to do this same trick, but with a different color. Pick another spot on the painting, and focus your mind there. I can’t promise that lines will start to appear, or disappear, but we can still ask the same questions: What rhythm do you feel? How does the color operate across the painting? What realities, real or imagined, does it present you with?

In a later part of the same interview, when asked about the musical nature of his pieces, Davis responded. "I guess it's awfully hard to accept the idea that my work is abstract. Actually, it's non-representational. The stripes are the subject matter."

And this I think really gets to the heart of my problem with the "perception is the lesson" theory of illusion. To say that the audio says this or that, Laurel or Yanny, or that the image is a rabbit or a duck, is to miss the subject matter of illusion entirely. The subject is not what you perceive it to be; The subject is you, trapped between your perceptions and the reality, able to mold the one by squinting differently or thinking a different word, while the other remains unchanged. And this is where we can begin to realize that the real isn't even the subject matter. The real is abstract. The rabbit duck, or the Laurel Yanny sound bite, these things are only as grounded in their reality as our perceptions contextualize them to be. That image and that audio are just lines and shadows, waveforms on a digital recording, sound and fury, signifying nothing, until we give them something to signify, give them a world to live it, pick a perception to view them through.

I guess it is all about perspective.

Or at least, that's the way I see it.

Is your brain tickled yet?

Sources:

Quotes in the episode and my research all came from an interview between Gene Davis and Donald Wall, which is published in Gene Davis, edited by Donald Wall. New York, Praeger Publishers, 1975.

Music:

Heliotrope from Aeronaut by Blue Dot Sessions

Waterbourne from Algae Fields by Blue Dot Session

In Paler Skies from Aeronaut by Blue Dot Sessions

Special Thanks:

Our special thanks this week goes out to Lauren LaPorto. She has joined the team to help with some of the marketing and social media parts of the show.

Credits:

Our theme music was performed by Mike Harmon, with recording, editing, and mixing from Casey Dawson. Our show art was made by V Silverman. The script is turned into a transcript by Amanda Borglund. This episode was produced, written, recorded, and edited by T.H. Ponders.