18: 1943- Nightlife

Content Warning: This episode contains discussions of racism, race riots, racial violence, police brutality and war. Please take care of yourselves while listening to the show or reading the transcript below.

Join us at a juke joint just around the corner from Hopper's Nighthawks, as we take a look at Archibald Motley's joyous, yet poignant reaction to World War II, Nightlife.

This episode features the voices of the following creators. Please check out and support their work!

TK in the AM and Weeksvile by Keisha TK Dutes and Conscious, the voices of the patron and James the Bouncer.

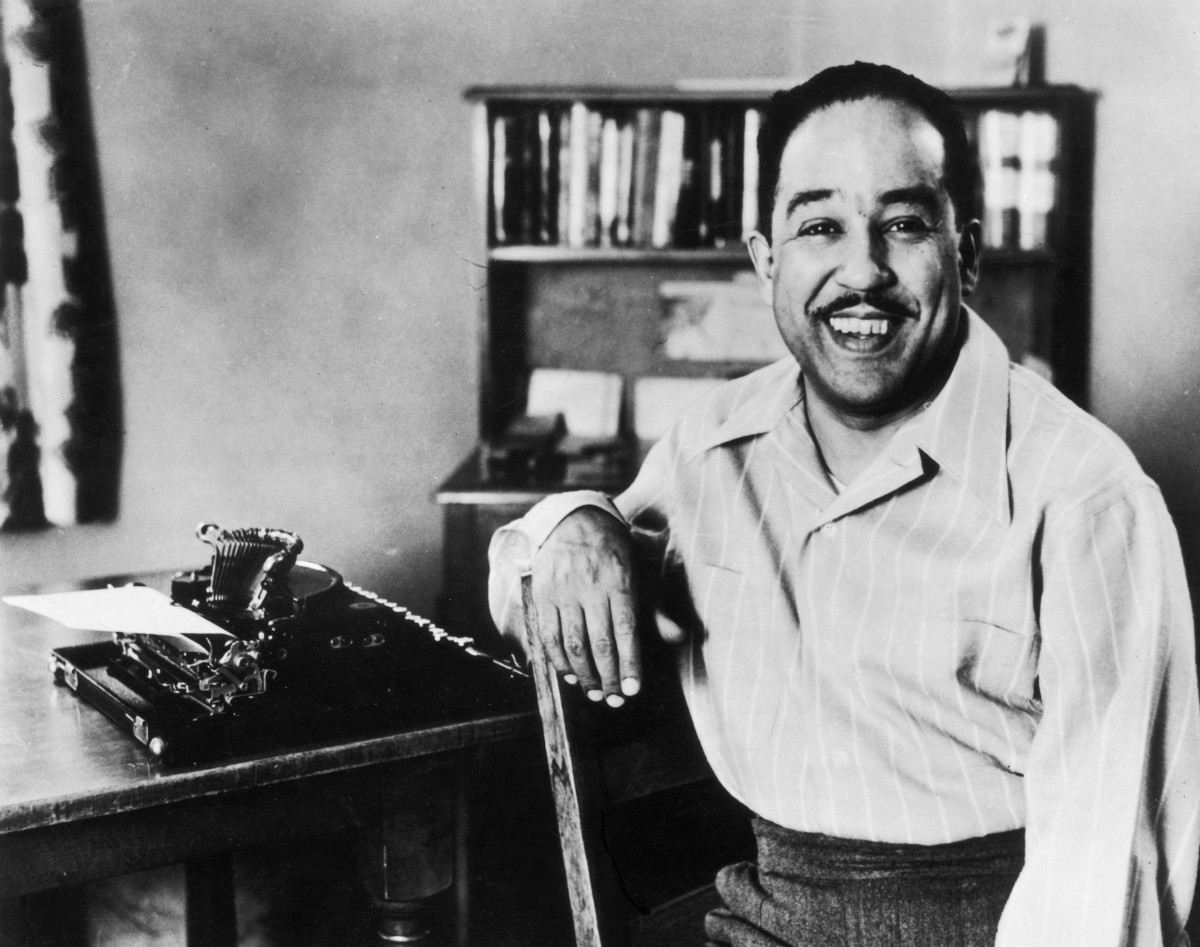

Flyest Fables by Morgan Givens, the voice of Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks.

Time Well Spent by Ronald Young Jr., the voice of Alain Locke.

Welcome to Accession. Today we’re at the Art Institute of Chicago, in Chicago, Illinois. Actually, we’re going to go almost exactly the same way we went when we came to visit Nighthawks. Enter the museum, go straight on, under the stairs, through the Buddhist and Hindu art, say hello to Ganesha again, find your way back past the courtyard with the greek sculptures. From there, head to your right, and up the stairs into the American Wing. This time, however, you’re going to go to the the second gallery on your right, not the first. From this room there should be a spot where you can see Nighthawks through the opening to the next room, and on the wall that makes that opening, you can see the subject of our episode. Today we’re going to enter Chicago Art Institute Accession 1992.89, Archibald Motley’s Nightlife.

Ponders: 1943. A spring night, well after one, pushing towards two. A jazz club in Bronzeville, on the South Side of Chicago, in the imagination of Mr. Archibald Motley Jr.

[Footsteps walking closer to a club, with the gentle din of a crowd and a band playing Blues in the Night.]

Bouncer: Excuse me ma’am, you’ve got to leave that out here.

Patron: What? Leave what out here?

Bouncer: Is this your first time at Motley’s Nightlife?

Patron: Yeah, I’m in from New York for the weekend.

Bouncer: Oh! We got Jimmie Lunceford here from New York as well. But, this place is a little different. We don’t allow that stuff inside.

Patron: What are you going on about?

Bouncer: Jim don't crow here - ain't no paper bag party either. No stress, no worries, just a damn good time.

Patron: You don't know a thing about MY worries.

Bouncer: I can see it there, draped on your shoulders. Heavy burdens. You carry 'em with you everywhere you go. But here you got to put them down. Step inside. See what it's like.

Patron: Ohhhh... You mean I can just put 'em down here in this this pile with the rest?

Bouncer: Yes ma’am.

[The patron drops her burdens to the ground.]

Patron: Mmmmmmhm.

Ponders: She felt her shoulders raise, her back expand, her chin lift ever so slightly, as she walked without the burden on her shoulders, into Motley’s Nightlife.

Patron: Hm. That’s much better. Thank you!

Bouncer: Of course. Have a nice night ma’am.

[The sounds of people drinking, and dancing, under a particularly intricate jazz solo that takes us from the instrumental Blues in the Night to the sung version of the same tune.]

Ponders: Her eyes were immediately filled with people of all sorts. A couple sits near the door, taking a break from the dancing to get a draft of the cool spring air everytime a new patron enters. The man smiles and closes his eyes when the door opens, sighing in the momentary relief. They’ve found a nice spot to take a break from their lindy hop and continue their other dance over drinks.

Behind them, a couple... dance the jitterbug? Or at least he’s trying. His steps are way too wide and his shoes clunk against the floor with every beat. He seems to be enjoying it but she’s... well... But now a well dressed man with a flat cap reaches out a hand with a cigarette between his second and middle fingers, to offer her some relief. She’s too polite though. She’ll finish this dance and then take him up on his offer.

The crowd goes ten or twenty deep behind them, all drinking and smoking, mooching and grinding. One couple does the local strut in place, while another does a pastiche of a tango across the floor. The only thing you can say about them all is that they’re all smiling. Jimmie Lunceford is in from New York tonight, but even if he wasn’t here, the walls would be thumping with that raucous swing that coats the whole world in that unnatural, beautiful magenta glow.

Behind the bar, one man twists the bottles so the lights can make their names visible to the inebriated customers. Still another cuts off the woman in front of him and the head off the beer, both having foamed over the edge. And next to her sits a woman in bright emerald, with a red beret tipped up. She’s clearly grown bored with the drunk girl next to her, and maybe even the whole crowd, and is relieved to see some fresh company as our New Yorker enters the scene. She sees the girl in green smile, and decides to take a chance on the empty barstool next to her.

We’ll leave ‘em to it. Let’s step outside for a smoke, and talk about Mr. Motley.

[Footsteps and the door creaks, as the bar fades into the background. Ponders fumbles with a lighter.]

Bouncer: Ponders, you’ve got to take that with you.

Ponders: Oh come on James, I’m only out for a smoke. You know I wont leave without it.

James the Bouncer: Them’s the rules Ponders. I don’t make ‘em, I just keep ‘em

Ponders: Oh alright. Mine’s not as heavy it’s just awkward. The white male privilege takes a few pounds off but the white guilt is big and bulky.

[Ponders pulls their burdens out of the pile and puts them up on their shoulders.]

Ponders: Anyways, as I was saying, Mr. Archibald Motley Jr. is the proprietor of this establishment. It’s well loved. It’s got it’s regulars, and its passers bye who are all are caught in its gorgeous glow. Of course, at one point every regular was just a passerby caught, knowing they would never pass by again. But still others don’t let it work on them. They’re here for the more popular establishment that’s right around the corner.

Motley actually painted Nightlife in 1943, after visiting the Chicago Art Institute and seeing Hopper’s Nighthawks. You can see where he gets the unnatural lighting, maybe the pose of the bartender, and the voyeuristic perspective; but other than that, there is little held in common between the two.

James the Bouncer: I’d like to add that the other thing you’ll often hear about the Nightlife is about the colorism, or rather the lack thereof. For those who may not be aware, colorism is discrimination based on not just race, but the hue and shade of a person's skin, where a person with a darker shade of skin is treated different, and usually worse, than a person with a lighter shade of skin. Being of mixed race himself, French and Creole, and having a much lighter skin tone, colorism was a theme in many of his paintings. There are other pieces you can see where Motley dives into colorism in much more depth, but you can see those ideas here in Nightlife as well.

Ponders: Oh good catch. Thank you James. These are the sorts of quips you’ll so often hear about Nightlife. The rest of the story? It gets a little bit complicated. We’ll have to really understand both Motley and the world he lived in, if we truly want to get not only what this painting is, but why Motley painted it, and what it has to tell us. Let’s take a walk around the block, away from Nightlife, and when we get back, I’ll leave the choice up to you as to whether or not you’d like to go back in or continue on.

[Footsteps, as Ponders walks away, and the bar fades from the imagination.]

Archibald Motley’s story starts in 1891 in New Orleans, Louisiana, when he was born to an upper-middle class family, of mixed race. But the upper-middle class mixed race families in New Orleans were starting to feel the pressures of the Jim Crow laws, and folks fled for better lives elsewhere. So at three his family moved up to Chicago, which Archibald would call home for the rest of his life.

Now for some of you who are more familiar with American History, you may be thinking that this has something to do with the Great Migration, the massive movement of the African American diaspora out of the south and into the Urban Centers of the West, Midwest, and Northeast. That however wouldn’t happen for another 20 years, and it’s important to note that Motley’s family had a sort of “we did it first” mentality about the Great Migration. They had moved from a well to do neighborhood in Louisiana to a well to do neighborhood in Chicago. They didn't want to be associated with the migrant population, who was falsely understood to just be opportunity seekers as more jobs opened up during and following World War One. But while his family tried hard to separate themselves from the Great Migration, Archibald Motley name would forever become entangled with its greatest product, the Harlem Renaissance.

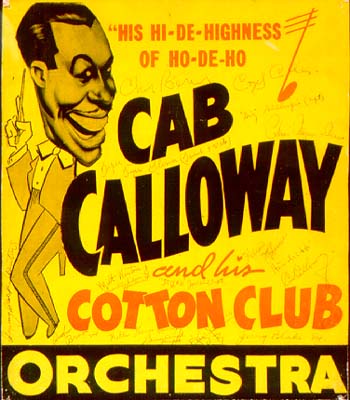

As working and upper middle class African-Americans moved into urban centers, and middle class whites began a steady move away from the urban centers, neighborhoods like Harlem became something that America hadn’t experienced much before: Harlem was a community designed and lived in by African Americans, where their culture was allowed to thrive. Music, literature, art; Cab Calloway, Langston Hughes, Augusta Savage, all found themselves in this corner of Manhattan where they were free to create, and draw upon their experience and the experiences of their parents and grandparents.

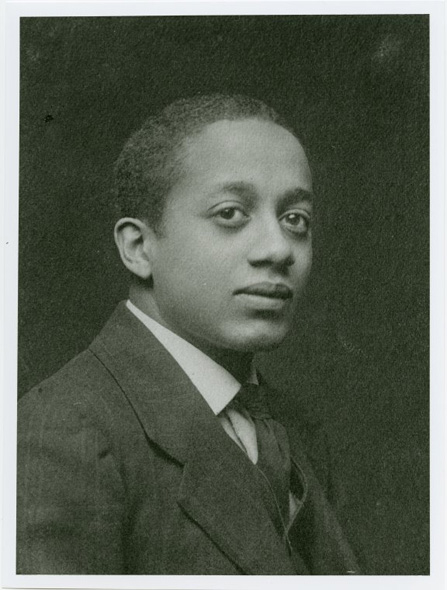

As a sidebar, it wasn’t referred to as the Harlem Renaissance at the time. Most referred to it as the New Negro Movement, a name which had been around for a while, but gained a particular popularity after a series of essays were published under the title “New Negro Movement” in 1925 by Alain Locke. This concept of the New Negro was meant to differentiate a new mindset for African Americans, one that would help unshackle them from the stereotypes, and stereotypical characters, that had been ascribed to them.

As Locke says “By shedding the old chrysalis of the Negro problem, we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation. Until recently, lacking self-understanding, we have been almost as much of a problem to ourselves as we still are to others... With this renewed self-respect and self-dependence, the life of the Negro community is bound to enter a new dynamic phase, the buoyancy from within compensating for whatever pressure there may be of conditions from without. The migrant masses, shifting from countryside to city, hurdle several generations of experience at a leap, but more important, the same thing happens spiritually in the life-attitudes and self expression of the Young Negro, in his poetry, his art, his education and his new outlook, with the additional advantage, of course, of the poise and greater certainty of knowing what it is all about.”

It’s an incredible idea, beautiful even. As you might expect though, the execution wasn’t quite as unifying, with some people embracing a culture that blended the eurocentrism that built the cities around them and the afrocentrism that they had clung to for a sense of identity, while others sought instead to focus on building African American culture independently, as a form and culture of its own.

Of course, calling this time period the “New Negro Movement” is slightly more appropriate given the fact that is occured all across the country, not just in Harlem. And each contingency having its own name for it, like the arts movement that sprung up out of the black belt along the South Side of Chicago, which was called the Chicago Black Renaissance.

During this period of time, Archibald Motley would study at the Art Institute in Chicago, he would show off works in New York, and he would eventually receive a grant to travel of Paris and study art, all while keeping his home in the upper middle class black neighborhood on the north side of Chicago. If you look immediately to your right, you can actually see one of Motley’s paintings from this time period. While he wasn’t totally isolated from the communities like Bronzeville that were developing at the time, he still held some remove from them. He painted black urban scenes and black subjects, but he painted them with traditions and techniques he had acquired in the Art Institute and Europe, and he sold them to white audiences. If you can’t tell, Motley wasn’t afraid to mix his Eurocentrism and Afrocentrism.

Blues, Archibald Motley Jr., 1929, Art Institute Chicago.

This is where the divide begins. I’ve brought all this up because when you search out information on Motley, the first words you’re bound to see are “Harlem Renaissance.” And when you search for information on “Harlem Renaissance Artists” Archibald Motley’s name is going to appear near the top of that list. And yet, Motley didn’t live in Harlem, didn’t even live in the neighborhoods of it’s Chicago contingency, nor did he embrace the some of the core beliefs of the majority of the movement. At one point, Motley is even quoted as having said that the Harlem Renaissance never actually happened. None of which I bring up to discredit Motley, but simply as a reminder that Motley was not a part of some homogeneous cultural movement, the way that the Harlem Renaissance, and black culture in general, is often presented. And all of these points going through Motley’s life are important; not really having one race, but being a part of the racial minority; moving North before the Great Migration, but being a part of the larger cultural migration; not really being a part of the Harlem Renaissance, but also being a critical part of the greater cultural Renaissance. His involvement and separation in each of these cases will perfectly prepare him to paint Nightlife, as the Harlem Renaissance comes to a close sometime around when most things closed down in this country, and Motley, like the rest of America, found himself on the home front of World War 2.

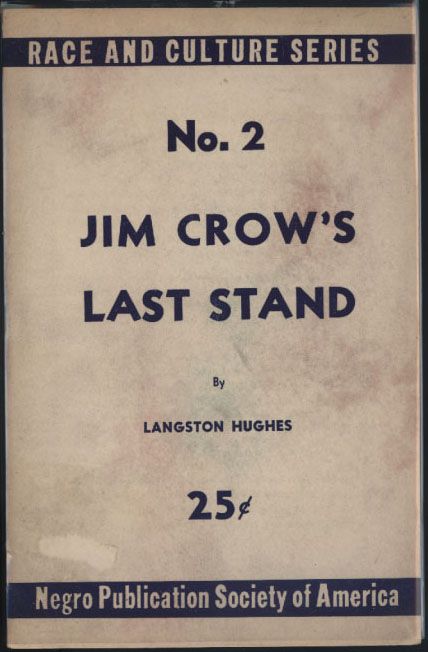

As factories were converted from peacetime manufacturers to mechanism of war, the country witnessed another migration to the urban centers out of the South, as there was once again a need for workers. That summer there were five different race riots; Mobile, Alabama in May, Beaumont, Texas, Detroit, Michigan, and Los Angeles, California in June, and Harlem, New York, in August. Your history books might talk about the Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots, but I would be surprised if they give any mention of the other four. They kind of betray the picture-book of a unified American Homefront. And if your book does mention them, they’ll probably wax about how the cities were just too crowded, the hours just too long, the tension just to high. They’ll likely skip over the continuation of Jim Crow segregation imposed by white communities, the part where white shipyard workers attacked and pillaged Black communities in Beaumont, the white police officers who brutalized black youths in the streets of Detroit, or the white police officer, James Collins, who shot and seriously wounded Robert Bandy, an African-American veteran in Harlem. The history books may not tell you these things, but Langston Hughes wanted to make sure you knew. Pick up one of his collections, and you might find…

Beaumont to Detroit: 1943 by Langston Hughes

Looky here, America

What you done done–

Let things drift

Until the riots come.

Now your policemen

Let your mobs run free

I reckon you don’t care

Nothing about me.

You tell me that Hitler

Is a mighty bad man.

I guess he took lessons

from the ku klux klan.

You tell me Mussolini’s

Got an evil heart.

Well, it mus-a been in Beaumont

That he had his start–

Cause everything that Hitler

And Mussolini do,

Negroes get the same

Treatment from you.

You Jim Crowed me

Before Hitler rose to power–

And you’re STILL Jim Crowing me

Right now, this very hour.

Yet you say we’re fighting

For democracy.

Then why don’t democracy

Include me?

I ask you this question

Cause I want to know

How long I got to fight

BOTH HITLER–AND JIM CROW.

Chicago escaped the race riots. Its mayor, Edward Kelly was a good friend of FDR’s, very much in favor of the war, and worked carefully to make sure that his city followed Executive Order 8802, Roosevelt’s move to eliminate discrimination in the U.S. Defense industry. Of course, Kelly was mostly thinking politically. This was a chance to get the black voters of Lincoln’s Republican Party over into Roosevelt’s Democratic Party. But nonetheless, conditions were manageable, and the city got along mostly peacefully.

I say mostly. There was still a war going on after all. And those loses hurt all of the communities in Chicago, especially the African American community. In her book of poetry, A Street In Bronzeville, Gwendolyn Brooks laments over the identity and life being stripped from African-American Soldiers who were now just soldiers, or now just dead, in her poem...

still do I keep my look, my identity... by Gwendolyn Brooks

Each body has its art, its precious prescribed

Pose, that even in passion’s droll contortions, waltzes,

Or push of pain— or when a grief has stabbed,

Or hatred hacked— is its, and nothing else’s.

Each body has its pose. No other stock

That is irrevocable, perpetual

And it's to keep. In castle or in shack.

With rags or robes. Through good, nothing, or ill.

And even in death a body, like no other

Or any hill or plain or crawling cot

Or gentle for the lilyless hasty pall

(Having twisted, gagged, and then sweet-ceased to bother),

Shows the old personal art, the look. Shows what

It showed at baseball. What it showed in school.

[Footsteps again.]

And sometime, amidst all this, Archibald Motley walked into the Art Institute, saw Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks and was inspired to paint Nightlife.

[Nightlife returns to the imagination, with Jimmie Lunceford behind the door once again.]

If we look at these three next to each other, on the surface, one of them doesn’t seem to belong. Hughes wake up call to a broken America, Brook’s lamentation for the fallen in her community, and Motley’s joyous depiction of a night club, hopping to the swing into the late hours of the night. But in a way, Motley’s piece falls right in line with the other too. And, even more ironically, it’s those elements from Hopper that help this be the truly rebellious piece that it is.

We’re not quite across the street looking into the diner, but Motley does paint us at a remove, much as has was at a remove. Perhaps we’re standing in the doorway looking in, but we’re not truly in the scene. If you look to your right again, you know what it’s like to really be in the scene of a Motley. But here there is distance. We might argue it’s the distance Motley felt from the community, not living in Bronzeville, or the distance he felt from his own identity with relation to his race. As a white person, I’m not really equipped to make or affirm those readings. But there is one reading I think I can present. This distance is a distance from joy. It’s there. We know what it looks like. We know what it feels like. We can hear it in our ears and feel it thump through the floorboards. We could even see it in the twirling motion of the Lindy Hop but then...

[The music stops.]

Frozen.

Motley traps the whole world in this brilliant magenta light, unnatural even, just like the lights spilling out of that other diner. Because maybe it’s not natural. In this time, in this age, hell, in any time, in any age, no matter who you are, the joy will never be as pure as it is here, in this bar, in this moment frozen in magenta light.

[Nightlife reappears.]

So that’s what Motley has to offer; a glimpse at a better world, and he’s not wrong to paint it. Far from it. It’s slightly anachronistic, but it as important to tell stories of black joy and love as it is to tell stories of black struggle, and then to give people a choice.

Because again, we’re standing at a remove. You have options as to how you interact with what Motley is putting before you, and it’s going to differ based one how heavy your load is. You could ignore the world you’ve seen here and try to move on with your life, but you’ve been listening to me for this long, so I don’t imagine that’s an option you’re interested in. Or you could take this as a starting point, a goal, a world you want to see not just in this bar, in this painting, but out here on the streets, in the real world, as well. That means we need to figure out someway to get rid of these bags, or at least lighten them, and not just for ourselves but for everyone. And that’s a much bigger question and one we can talk about another time. But your final option is to go in. Enter the painting. Embrace the joy that Motley’s offering. Live in this place and be happy for just a little while. It’s actually the most important thing this place can offer; a breather, a recharge, a reminder that there is good in the world.

I mean this in all seriousness, I will not judge you if you want to spend the next few minutes in Nightlife. I think Jimmie’s about to play one hell of a tune and the floor is bound to shake. But I’ve been in Nightlife for a little to long for my liking. It’s time for me to walk this road, work on finding those solution. If you’d like to join me, you can turn down your volume and sit in silence for a few minutes, to reflect on how you’re going to bring more joy and more justice into your world. But if you’d like to experience Motely’s joy and live in it, leave your volume up, and enjoy.

Ponders: Have a nice night James.

James: Goodnight Ponders.

[Footsteps, as Ponders walks away. James holds the door open for you, and the band begins to play T’aint What You Do, It’s the Way That You Do It.]

Sources:

Information on Nightlife from Archibald Motley Jr. and Racial Reinvention: The Old Negro in New Negro Art by Phoebe Wolfskill, and from the publications on the work by the Art Institute Chicago.

Quotes taken from The New Negro by Alain Locke, Collected Poems by Langston Hughes, and A Street in Bronzeville by Gwendolyn Brooks.

Music:

Blues in the Night- Jimmie Lunceford

It Had to be You- Jimmie Lunceford

Twelfth Street Rag- Louis Armstrong and the Hot Fives

Says Who? Says You, Says I!- Cab Calloway

West End Blues- Louis Armstrong

I’m Afraid (Of Loving You Too Much)- Duke Ellington

I’m Gonna Move To The Outskirts of Town- Jimmie Lunceford

For Dancers Only- Jimmie Lunceford

T’aint What You Do (It’s The Way That You Do It)- Jimmie Lunceford

Special Thanks:

Keisha TK Dutes is the voice of the Patron and Conscious is the voice of James the Bouncer. You can find out more about their radio show TK in the AM and their soon-to-be released podcast project Weeksville on their website at www.bondfireradio.com.

Morgan Givens is the voice of both Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks. You can find out more about his excellent Children’s Audio Drama, Flyest Fables, on his website at www.morgangivens.com.

Ronald Young Jr. is the voice of Alain Locke. He also hosts the incredible Time Well Spent podcast. You can find out more about his work at www.ohitsbigron.com.

Credits:

Our theme music was performed by Mike Harmon, with recording, editing, and mixing from Casey Dawson. Our show art was made by V Silverman. This episode was produced, written, recorded, and edited by T.H. Ponders, with additional dialogue and sensitivity editing from Keisha TK Dutes, Conscious, and Ana Madsen.